- What can the consensus makers

- of Europe do for Iraq?

Consensus building is the subtle and laborious process of haggling and compromise amongst participants of dissent, so that everyone can walk away from the table with a net gain. A necessary chore in any democracy, it is especially critical amongst the heads of government across Europe. An American president enjoys constitutional powers inherent of his own office. While his actions can be checked by an elected assembly, his agenda are his own, not subject to consensus amongst the members of Congress. This is not the case in, say, London, where the prime minister is a member of parliament, whose executive decisions must always be approved by a majority vote. The presidencies of Italy and especially France are closer to the American system, but even they do not wield exclusive authority, but must form a government via a prime minister, usually with a coalition of diverse political factions as mandated by a general election. |

||

|

|

Because an entire government hangs on the the balance of just so many

parliamentary votes, consensus is of paramount importance to an Eurocrat. His own voice is

seldom heard above the din of parliamentary debate; her ideas are often

obscured in diplomatic vagary to accommodate everyone.

In America, speaking plainly and standing up for one's own values is a virtue; in Europe it is an eccentricity. Indeed, the uglier aspects of governing by consensus inevitably involve compromise of one's moral convictions for the sake of political expediency, or endemic corruption amongst politicians who form a potent bloc. |

|

|

Governing by consensus does have an advantage: it is a defense against demagoguery, precisely because consensus builders obligingly subvert their personal charisma into mutual benefit. In a continent that has seen Napoleon's rampant warmongering in the name of liberty, equality and fraternity, or the insidiously legitimate ascendancy of Adolf Hitler, Europeans are wary of any overbearing politician who wishes to impose a private agenda upon a consenting populace. By sheer personal will, and without the encumbrance of consensus at every step, George W Bush could push for war in Iraq as far as he has done, earning the admiration of many and the loathing of many more from around the world. Neither he nor, for that matter, Saddam Hussein is the most interesting character in this unfolding crisis. To the very end, both are apparently giving a very predictable performance, acting quite unerringly to the scripts handed to them since day one. |

||

|

In this drama, two players deserving more scrutiny are

Jacques Chirac and Tony Blair. The former

is noted for his unabashed challenge of consensus politics; the latter for

his commitment thereto despite its unfavorable outlook.

Chirac won his current term in 2002 as a popular mandate against the reactionary right, in a harrowing run-off election against the xenophobic candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen. A decades-long veteran of the nasty rancor that is French politics, Chirac did not survive his last election completely unscathed, as he is still dogged by unresolved allegations of fiscal impropriety, which he had brushed aside on the ground of "presidential immunity." Unshackled from the uneasy "co-habitation" with defeated Socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin at long last, Chirac is now free to personalize the condescending and demagogic rhetoric of "ideals" and "moral standards" to bolster his formidable political stature. |

|

|

When a leader finds consensus politics unnecessary, either due to his privilege of power or simply because everyone appears to agree with him, it becomes more difficult to tell whose interests he is actually serving. Why Bush really wants to attack Iraq will always be open to speculation: there is Bush Jr's vendetta-like mentality regarding Saddam and his dad George H Bush over the first Gulf war in 1991, as well as the cabalistic alliance between the Bush-Cheney administration and the American big energy companies, which naturally covet the world's second largest oil reserve in Iraq. (VP Cheney, to this day, refuses to disclose how he and other fellow energy tycoons have deliberated upon the nation's energy policy behind closed doors back in 2001.) The point here, though, is that Bush is entitled to act on those unstated agenda, so long as he can argue that he does so in the interest of international security. For a world still reeling from 9-11, it is a cheap argument. Here is another. For most people on earth, the notion that America (the world's sole superpower) and Britain (formerly Iraq's colonial overseers) would forcefully violate the sovereignty of an impoverished, pacified and non-hostile Arab state is absolutely intolerable. One can find no cheaper political capital in this, as Gerhard Schroeder demonstrated in his narrow victory last year, promising the German voters not to get involved in Iraq. It was a classic play of consensus: without the anti-war stance, the chancellor would not have been able to get the votes for his feeble center-left platform, and form a coalition government with Joshka Fischer and his Green party. |

||

|

Chirac, already safely ensconced at Champ Elyssee, could afford not to

redeem this political capital. Had he sided with US and Britain, he would have

angered much of his electorate -- including an economically marginalized Muslim

population, the largest in Europe -- but could also have staked additional interests in Iraqi oil, for which the

French energy sector had invested heavily. Since Spain and Italy were

already in favor of the Anglo-American initiative at the onset, doing so would

consolidate European support and minimize any dissent, averting a diplomatic

crisis in the UN Security Council and NATO. On the other hand, opposing a war that might never happen can keep more people alive, lead a favorable majority at the Security Council, win a Nobel peace prize, and secure the oil interests with far greater certainty. |

|

|

A compromise between the two camps, in the spirit of consensus building, could also be feasible: France could abstain from rather than veto against any vote in the Security Council that authorizes war, while agreeing to provide the US and British forces with intelligence and logistical support befitting a NATO member. Had a compromise taken place, Americans would not be ordering "Freedom Fries" and "Freedom Toast." Chirac chose, as the Bush did, to stand his ground. For that he is to be commended, perhaps not as a matter of conviction, but as an ostentatious departure from politics-as-usual in Europe. Discarding vagary and compromise, Chirac became the definitive -- and dominant -- advocate against the war. |

||

|

|

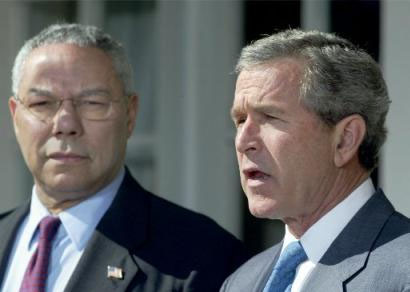

How

the bully pulpit is used by the French president and the British prime

minister is a study in contrast, not just for their obvious differences of

opinion. Chirac, along with his Foreign Minister Dominique de Villepin,

appear serene and magisterial before the world, as assured of their

righteousness as Bush and Colin Powell, the Secretary of State. When the

cameras turn to the haggard features of Blair and Foreign Secretary Jack

Straw, however, it is the image of two overworked bureaucrats against

the backdrop of a contentious House of Commons.

More than anyone else, Tony Blair tries to make consensus politics work in favor of the Anglo-American initiative against Iraq. He has no choice: his central-left Labour Party, already split over the issue amid public opposition to war, can evict him from 10 Downing Street at any time with a vote of no confidence. |

|

Blair's rise to the top job is attributed both to his resilience under the long shadow of Margaret Thatcher, and a complacent Conservative Party perennially mired in sex and money scandals. Blair did not turn the clock back to a socialist Britain, but diligently campaigned to convince the British electorate that his party was better qualified to carry on the fiscally and socially conservative policies indelibly established by his redoubtable predecessors. Theoretically, a British prime minister has broader sway over policy than an American president, because the PM is necessarily the majority leader amongst the lawmakers of the land. Blair never truly enjoyed this advantage, however. The New Labour did not start their reign with a pompous manifesto, a la Newt Gingrich, et al's "Contract with America" when the Republicans took over both houses of Congress for the first time since anyone can remember. Such a grand gesture would be counter-productive in a party that was, in effect, a coalition of Labour's traditionally-left elements (the labor unions and the public sector) and those much further to the right (business interests). Well before Bush's "axis of evil" speech, well before 9-11 itself, Iraq was already a large blip on the British radar screen. Britain made a bid -- ultimately futile, in light of subsequent developments -- for "smart sanctions," easing limitations on the trade embargo that devastated the Iraqi economy as a whole, but left Saddam's regime intact thanks to its control of oil. Blair and Straw traveled all over Europe and the Middle East, trying to build consensus for a policy that was certain to become an effort of compromise. It was a little something to appease Western conscience for having made the lives of an oppressed people even more miserable. |

||

|

|

This

led many to believe that, unlike Bush's suspected vendetta or oil

interests, Blair genuinely wanted to oust Saddam for the deliverance of the

Iraqi people.

The British certainly did not need Iraqi oil as badly as the Americans, or to recover their investment in Iraqi oil as much as the French and the Russians. In Europe, Blair bore the brunt of much criticism for being subservient to foreign policies issued from Washington, even as the PM insisted that he was not taking orders from the White House, directly or otherwise. A continent that is generally anti-war simply cannot accept the idea that any enlightened European leader would sincerely desire a war in Iraq. |

|

Does it really all matter in the end? If the Europeans feel it is not in their interest or moral rectitude to fight a war in Iraq, what can they do when the Americans do go to war without them, anyway? (Of course, the Americans are never alone. Britain will begrudgingly keep its commitment, Spain, Italy, Denmark and far-away Australia will give their token support, and then there are the new and prospective EU members like the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, who are eager to associate themselves with -- and reap benefits from -- the United States. And yes, don't forget the Iraqi opposition, the vengeful Kurds of northern Iraq and the Kuwaitis.) The entrenched positions taken by Iraq and the US are apparently beyond compromise, give or take another day for Saddam to "reconsider" disarmament and resignation (and for the 62,000 American troops initially bound for Turkey to cruise down the Suez, the Red Sea and around the Arabian peninsula). What good can Chirac's hauteur of peace or Blair's quixotic quest for consensus do? A lot, actually. Assuming the invasion is indeed swift, fierce and decisive, France, Germany and other hesitant allies -- the whole of UN -- must then come together to rebuild Iraq. Tasks such as peacekeeping, repair of Iraq's main infrastructures, and the transition of political institutions must be dealt with the utmost urgency and care. The Iraqi people might be more receptive to the assistance of those who refrained from dropping bombs onto their homes in the first place, but are there now to give humanitarian aid. Here, then, the skills of consensus building would be needed once again, to piece together a defeated, divided and restive coalition of southern Shiites, central Sunnis, northern Kurds and Turkmen under the auspices of the United Nations. The victorious allies must convince themselves, and their own constituents, to commit sufficient resources for this daunting endeavor. There will indeed be more haggling, compromise and unrealized aspirations amongst needy and the well-intended. The consolation is that the daily new headlines will be more palatable. George Bush can holster his guns, bringing home the hundreds of thousands of servicemen and women. Jacques Chirac can act on his superior sense of morality. Tony Blair -- if he's still residing at 10 Downing by then -- can resume doing what he does best, building consensus where none seems possible. Charles Weng, 14 March 2003 |

||