|

| 20 July 2016: A civillian, one of more than 58,000, being detained in Turkey, following the 15 July coup attempt. (BBC / Associated Press) |

Nightmare in Turkey

Here are two handy rules to tell if a democracy is failing:

If an elected chief executive remains in power for more than a decade, he is an autocrat.

Immediately following a military coup, whoever in power is an autocrat.

The logic is quite simple. Should an incumbent leader hold onto power for that long, he must assert extraordinary authority to control a polarized electorate that is deeply divided between a fiercely loyal following, and a bitterly frustrated opposition. He will have already changed the laws to legitimize his extended rule.

When the generals deem it necessary to bring about regime change by force, the nation is essentially in a state of civil war, and whoever prevails will be compelled to vanquish his enemies under the harsh justice of martial law. That a putsch can even take place in the first place underscores the vulnerability of a nation’s elected government and other civilian institutions, ever weakened by despots and corrupt officials.

There have been, and still are, many recent examples of failed or faux democracies, ruled by juntas or presidents-for-life: Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Egypt, Syria, Russia, Myanmar, etc. Now Turkey is on this ignoble list.

Fourteen years ago, I was impressed with Turkey’s confidence in electing the AKP, a conservative, Islamist-leaning party, into power, ushering in a prime minister who vowed to uphold his nation’s secular and democratic ideals. The country had come a long way since its last military coup in 1980 to elevate its civil society to western standards. It even abolished the death penalty, the largest among the few nations with a predominantly Muslim population to do so (Bosnia, Albania, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan and later, Kosovo.)

Given its strategic, economic and historical significance to Europe, I argued that a democratic Turkey was qualified to join the European Union, then in the process of incorporating Bulgaria and Romania, Turkey's two Black Sea neighbors. Cyprus, farther east of the Prime Meridian than Istanbul, had just become a member (that is, until it split into two, with the Turkish-speaking half still unrecognized by any other nation except Turkey).

|

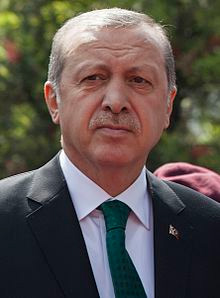

What a difference fourteen years make. Like Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdogan was also elected president after serving as prime minister, only that the Turkish leader had effectively transferred full executive power to a once mostly ceremonial position. Since then, he has squelched his opponents and critics, creating new laws to disqualify opposition candidates, and prosecute journalists as terrorists. He even built himself a lavish palace, fit for a dynastic dictator. Erdogan justifies his autocratic rule with the ongoing fight against his two great enemies. The Kurds in Turkey are always conveniently blamed for the nation’s political and economic woes, whenever militant groups among them -- in no way representing the Kurds as a whole -- have their intermittent insurgencies. Even as Kurdish fighters from Turkey, Iraq and Syria became the vanguard to resist the expansion of ISIL, Erdogan insisted on launching strikes against Kurdish targets. Thus, when no one is making friends amid the chaos of war, an enemy of the enemy is still an enemy. Both ISIL and Kurdish militants are now claiming responsibility for repeated terrorist attacks in Ankara, Istanbul and elsewhere. Then there is his feud with ally-turned-rival Fethulan Gulen, a cleric whom he accuses of instigating the failed July 15 coup that ended on the same night it began, when Erdogan called upon his legions of supporters to fill the streets of Ankara, Istanbul and other cities to confront the rebel soldiers, resulting in 232 people dead and 1,541 wounded. The paranoid Turkish president is convinced that Gulen, from his home in Pennsylvania, is running a "parallel regime" that is in the process of toppling his own. |

Assuming powers not seen since the days of the Ottoman Empire, Erdogan has ordered the dismissal of tens of thousands of civilian workers, who had no part in the uprising: 15,200 education ministry officials, 21,000 teachers, 1,577 university deans, 8,777 interior ministry workers, 1,500 in the finance ministry, and 257 in the prime minister’s office. This is done on top of the 7,500 soldiers, 8,000 police, and 3,000 judges that are arrested or suspended. The purge effectively turns co-workers, students and teachers against each other, pitting the vindicated AKP supporters against everyone else, and instilling more fear among the populace than the short-lived rebellion itself, aside from the immediate injuries incurred and losses of life.

Earlier, Erdogan’s regime exploited the ongoing refugee crisis that stemmed from the wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. It cut a deal with Brussels, agreeing to halt refugees from crossing the Aegean into Greece, in exchange for (1) cash assistance for the refugees’ immediate relief and eventual repatriation, and (2) visa-free travel of Turkish nationals in Europe, which hosts substantial Turkish expat communities, especially in Germany.

Given the current situation, the European leaders are not likely to honor their part of the deal for long. Even less likely is their consideration of Turkey’s application for EU membership, at a time when Jihadist attacks in France and Belgium have raised nationalist, anti-Muslim sentiment throughout the continent to an alarming height. It just so happens that Erdogan no longer cares about joining the EU.

I suspect that, should the Turkish authorities discover this obscure website of mine, it'd be wise for me not to travel to Turkey anytime soon.

(Source: BBC)

-- CW, 20 July 2016

| Back to top |

Cancilleria del Ecuador / Wikipedia

Cancilleria del Ecuador / Wikipedia