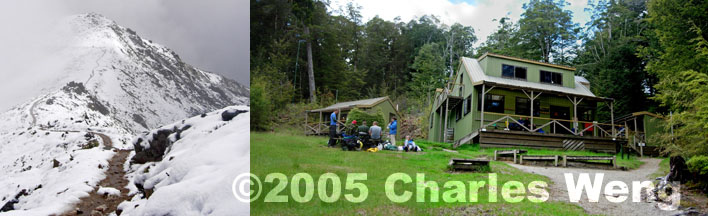

Kepler Track, Fjordland National Park, South Island. The mountaintops (left) between Luxmoore Hut and Iris Burn Hut see plenty of snowfall, even during the summer. The third hut, the Moturua (right), is idyllically situated on the shore of Lake Manapouri. Both pictures were taken during a three-day tramp of the 60-kilometer Kepler Track with a Nikon CoolPix 5200, set to automatic exposure at 7.8mm focal length, f/4.8 aperture, 1/2048 second shutter (left) and 1/263.5 second shutter (right).

The Great Race Row of New Zealand - Aotearoa(1)

November 2004 marked my fourth visit of New Zealand since 2001. It was my most daring journey to date, as I tramped for three long days along the 60-kilometer Kepler Track in Fjordland National Park(2), wagering against the unpredictable weather in one of the wettest regions on earth, as well as my own untrained lungs and legs.

As I took my chances with my immediate personal welfare to enjoy a stunningly beautiful landscape of fjords, alpine lakes, waterfalls and temperate rain forests, so do I risk the propriety of being an ever welcomed guest in this, one of the friendliest, most gracious societies I've ever encountered.

Here, with unabashed presumption, is my commentary on the national crisis the Kiwi media has dubbed "the Great Race Row." The moniker is somewhat hyperbolic, given the relative lack of such troubles there. However, despite that curious Anglo idiom that might led one to hope it's all just about a regatta (and crikey, do the Kiwis ever love their boat races), the true matter at hand is eerily familiar to anyone living in a heterogeneous society.

The majority, currently represented in government by the left-of-centre Labor Party and headed by Prime Minister Helen Clark, wants to assure long-term public access to the island nation's magnificent shorelines by means of nationalisation. This movement is loudly opposed by the Maori, who claim customary rights of ancestral ownership and cite the Waitangi Treaty of 1840, under which the British guaranteed the Maori rights to land, language and culture. Their objection, expressed in the country's largest public protest ever in a two-week march to Wellington this May, has angered the conservatives, who now openly profess their disapproval of any preferential treatment given to the Maori.

|

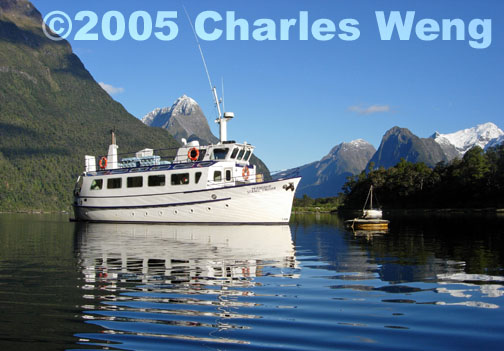

Milford Sound, Fjordland National Park, South Island. This photo of Real Journey's MV Friendship was taken aboard a floating kayak with a Nikon CoolPix 5200, set to automatic exposure at 7.8mm focal length, 1/812.7 second shutter and f/4.8 aperture. |

The Maori, making up 15% of New Zealand's 4 million citizens, have indeed enjoyed a kinder fate than most of their Polynesian and Aboriginal kindred elsewhere throughout the Pacific. Just as all official communications -- government documents, road signs and whatnot -- in Canada are presented in English and French, New Zealand has the appearance of a bilingual nation, a fact obvious to American visitors who think their flight has been diverted to Honolulu, when they try to read all the Polynesian signs upon landing in Auckland. |

Maori-spoken programmes with English subtitles, or vice versa, can be viewed not only on the state-run television channels, but broadcasts from an all-Maori station. Proportionately, there is far greater Maori presence in national government, academia and the local chambers of commerce than their Aboriginal counterparts in Australia. In the streets of New Zealand's cities and small towns, light brown complexions -- belonging to those of mixed European and Maori heritage -- are common sights.

Now, bad blood is being rhetorically spilt over the airwaves, as hostile factions speak of war, invoking the legend of Maori warriors killing and eating sailors serving Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. The historic political protest in May, resplendent with Maori pageantry, was derided by PM Clark, who dismissed its organisers as "haters and wreckers." Right-wingers are keen to attack a heretofore unknown "grievance industry," where the natives allegedly get more than their fair share of social benefits via public whining. Maori public figures are under siege, caught between their tribal loyalties and their services toward a supposedly integrated, egalitarian society.

For the good of the Maori and of the nation as a whole, this row must be resolved, lest it becomes more than a war of words. There must be a compromise. Yes, the Maori communities ought to keep their ancestral land rights. Yet they must be obliged to share their bounty amongst all New Zealanders, with both recreational access to their coastal lands (for the weekend picnickers, boaties and trampers that make up the justifiably idyllic stereotype of the Kiwi lifestyle), and as tax revenues from the profits of their proprietary use.

Earlier this year, whilst driving from Wellington to Auckland, I was quite dismayed to see graffiti of swastikas and vulgar variants of "go back to England" freshly spray-painted on rocks near scenic lookouts. This just won't do. If things do get worse, I will not return to New Zealand no matter how deeply I've already fallen in love with its lands, waters and its society at large. Such a place, dare I say, would be unworthy of its standing as Tolkien's Middle-Earth, even as I forgive Peter Jackson for the fact that Maori actors were cast only as the monstrous Uruk-Hai orcs or stunt doubles.

Long symbolised by the red poppy, 11 November is Remembrance Day in the British Commonwealth, including New Zealand and Australia. A day before, a Maori contingent were in France to receive the remains of New Zealand's only unidentified soldier that was killed in action during War War I. The Unknown Warrior, who served Britain in life and was honoured in the Maori tradition, is a fitting reminder that all Kiwis -- Maori, European and Asian descendents alike -- are united in one nation, under the flag of the Southern Cross. In this brief moment of remembrance, at least, one can forget all about the Great Race Row.

* * * * *

(1) Pronounced ay-oh-te-ah-ro-ah, the Maori name for their country means "land of the long white cloud."

(2) In America, hikers hike on trails. In Britain, walkers walk on paths. In New Zealand, trampers tramp on tracks.

[Fact source: BBC World Service]

CW, 26 October 2004, Updated 11 November 2004

| Back to top New Zealand 2002-2004 |