Leica

M6 TTL 0.72x

Leica

M6 TTL 0.72x

The first time I held an M6, I didn't know what impressed me more: the mystique and elitism that long preceded it, or the heft of brass, steel, chrome, leather and hand-polished glass from a bygone era. On New Year's Eve, 1999, I took one home to commemorate the passing of the millennium. It was to be the last film camera I would ever buy.

A Leica M and a lens -- that certainly set me back a dollar or two. To this day, I still own only two "basic" lenses, the Summicron M 35mm f/2 Aspherical and the Elmarit M 90mm f/2.8. Along with the camera itself, the handy SF20 flash and the requisite UV and polarizing filters, it's a mind-boggling $5K investment for a mechanical 35mm film camera outfit in the Digital Age.

I regret nothing. In New Zealand, while switching lenses, I dropped the 90mm Elmarit from my waist to the rocky ground. The chrome barrel picked up some blemish, and the focusing ring at the point of impact was nicked. Yet, thanks to its brass and steel housing (including the built-in steel hood shielding the front end), the precious glass elements remained perfectly intact, working flawlessly with the camera's meter and producing sharp, luminous exposures just as before. I am definitely looking forward to acquire my third Leica lens, whenever I can afford it.

As with the most coveted of Swiss wristwatches, Leica does occasionally allow style to supercede substance, refined as the latter may be. For those with really deep pockets, it is the cosmetic finish of the camera that directly affects its worth in the collector's market. There are limited editions with titanium bodies, special leather treatment, commemorative engraving or even 14k gold. If you want one with a specialized 0.58x or 0.85x viewfinder, however, you get the standard, no-nonsense solid black finish or, with less availability, the retro-styled chrome top.

The lenses are similarly delineated as well. Some are offered only in black: the 50mm f/1 Noctilux M, the fastest lens on earth, is too serious to be taken with touches of vanity. The chrome-finish lenses are slightly heavier and more costly than their black counterparts, due to their lens mounts being wrought in brass instead of steel. Lenses with matching titanium barrels for the limited Ti edition are most fetching indeed, but they command an exorbitant ransom for their rarity.

|

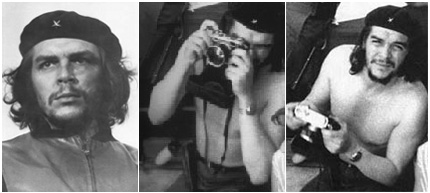

A familiar icon -- At left, the definitive portrait of Ernesto Che Guevara was taken in 1960 by März Alberto Diaz Gutierrez Korda with a Leica M2 and Elmar 90mm f/4 lens. Che himself was a Leica fan, as seen in the two casual snapshots taken with his family (photographer not identified). |

|

Once I start using my M6, I regard it less as a product of unabashed luxury, and more as a trusted tool. Its predictable, straightforward operation is never left to chance or carelessness. Since focus, aperture and shutter speed must be manually adjusted for each shot, I have no fear of ruining the exposure with an inappropriate camera setting, as I tend to do with my automatic cameras. The controls are precise, and yet simple: it's everything you learned in Photography 101, distilled into two rings around the lens barrel and one dial on top of the camera.

Such is the pleasure of using a rangefinder, the archetype of all point-and-shoot cameras today. With no need for a flipping mirror, it is typically smaller, quieter and less prone to camera vibration than a single-lens-reflex (SLR) camera. The subject remains continuously visible through the viewfinder during shutter release.

On

the other hand, rangefinders do not have the zooms, fisheyes, long telephotos,

tilt-and-shift's and other specialized lenses that make the SLRs much more

versatile. Towards either extreme of the focal lengths available to rangefinders

(Leica M lenses go from 21mm to 135mm), composition through the

constantly-sized viewfinder gets tricky. Long-range subjects must be composed in

a tiny rectangle, potentially compromising focal accuracy. Wide-angle views are

partially obstructed by the lens barrel. At 0.72x magnification, optics wider

than 28mm must be used with an accessory viewfinder, installed over the hot

shoe.

On

the other hand, rangefinders do not have the zooms, fisheyes, long telephotos,

tilt-and-shift's and other specialized lenses that make the SLRs much more

versatile. Towards either extreme of the focal lengths available to rangefinders

(Leica M lenses go from 21mm to 135mm), composition through the

constantly-sized viewfinder gets tricky. Long-range subjects must be composed in

a tiny rectangle, potentially compromising focal accuracy. Wide-angle views are

partially obstructed by the lens barrel. At 0.72x magnification, optics wider

than 28mm must be used with an accessory viewfinder, installed over the hot

shoe.

For me, the viewfinder isn't the greatest challenge. So many times have I incorrectly loaded film into my M6, I will always dread this chore. To preserve the rigidity of the round-ended camera body, the folks at Solms, Germany insist that you feed the film into a spool from the bottom, as it was done since day one at Wetzlar in 1914. Once I do get it right, my efforts are rewarded with prints of uncanny sharpness and luminosity, which defy depiction on a monitor screen.

Alas, even a Leica must fail in my hands at least once. During Summer 2000, the winder broke down in Tuscany, forcing me to extract and reload film in the closet of my Florence hotel room. (It's perfectly repaired now.) The fact that I could do so, and still acquire some decent images despite a little film fogging, underscored both the vulnerability and robustness of this mechanical camera.

After 18 years, Leica discontinued the M6 in 2002. At first the heir apparent appeared to be the M7, now featuring an electronically controlled shutter, aperture priority auto-exposure and DX reading. Then, stepping way back in time, Solms rewarded the ever-persistent purists with the MP, a fully-mechanical model that even did away with M6's TTL flash control.

The intrigue doesn't end there. Just as the joint venture between Leica, Kodak and Imacon produced the 12Mp, $5500 digital module for the Leica R SLR, they are now building a digital M from scratch, one that will continue to revel amongst the same peerless rangefinder lenses. If you opt not to spend the princely sum for this upcoming marvel, consider a Panasonic Lumix DMC-LC1 for $1250. It's essentially the same 5Mp camera as the $1850 Leica Digilux 2, both built around the same Vario-Summicron f/2.0-2.4 7-2.5mm lens.

|

|

An

heirloom – My father took many baby pictures of my older sister

and me with this Minolta Hi-Matic 9 rangefinder. The mechanical leaf

shutter of the built-in f/1.7 45mm Seiko Rokkor-PF lens (seen here with a

Walz UV filter) has a maximum speed of 1/500s.

Treasures from the past |

I bought my very first camera in 1990. The purchase, made with savings from my work-study stipends, was an Olympus point-and-shoot with a 28-50mm zoom and "panorama" mode (blinding the top and bottom thirds of the exposure).

Two years later, I bequeathed it to my dad when I upgraded to the Canon Elan, my first SLR, along with a 28-70mm zoom and a 80-200mm zoom. When my gear (which also included a Pentax weatherproof point-and-shoot) was stolen in Vancouver, BC in '94, it was my father who bought me a Nikon N90 and a Tamron 28-200mm zoom.

|

|||||||||||||||